Welcome back to this three-part series featuring one of the artists at Golden Road Arts, Oregon painter Erik Sandgren. In the previous lesson, Erik developed his painting and added color.

In the closing video of the series Erik makes his final revisions, and also discusses his influences in the fields of painting and printmaking.

Adding the Finishing Touches to a Landscape Painting Video

See how Erik Sandgren makes further revisions to his painting, “Fish Fishermen Rain Rainbow.” Track the progression of the artwork as Erik experiments with different colors and styles.

<

Materials Required for the Final Revisions of a Landscape Painting

- Paint

- Paintbrush

- Painting knife

To watch the entire series of videos, watch Charcoal Painting Part 1 and Developing a Landscape Painting Part 2.

Watch Erik Sandgren Complete the Painting

Read along with the video transcript to discover how Erik Sandgren experiments with different art styles. To see the best art from Oregon painters and printmakers, buy art online from Golden Road Arts.

One of the beautiful things to me about painting is that a given painting offers you different things at different distances. I love looking at JMW Turner’s paintings for that – his big paintings. There’s something for you there, whether you’re at 50 feet away or 20 feet or five feet away or three feet away. If they’ll let you get that close in the museums, there’s something there, you see things group up differently. They pattern differently.

So, in my effort to define that figure a little bit. I think I may have made that too – what would I say – just too contrasty and taking away from that center of attention over there. But that’s alright. I’ll put things in like that and then it’s there. I’m just that close to being able to quiet them again, which is absolutely wonderful to me. It never seems to be a miracle. There’re so many new and exciting ways to make art that have nothing to do with painting, but I have to admit I’m just still in love with painting and the immediacy of it. It’s accessibility to sight and understanding, the quickness of it. If you want to do something, you can do it now. You don’t have to wait. There’s no intermediary, no obstacle. You know, if you’re just kind of basically set-up the way I am here, you know, so all I need really.

Interesting, I think I’ve got too much going on up here. I’m going to take all of that, and I have a little medium that’s mostly a transparent medium, and I’m going to take that and try to convert that whole sky into some feeling of falling rain. A little bit of moisture.

And I guess the thing to me about painting and why I love photography as a documentary form and as its own art form. But photography doesn’t help me with the kind of painting that I want to do. The kind of painting I want to do has to do with translating vision into touch and gesture. And so, it’s kind of a dance, the way you work with the paint.

If I want that rain to fall, I’m not going to paint raindrops one at a time. I’m going to make a gesture about the whole thing coming down and make it happen. Make it happen. So, in the course of doing all that, I think it’s fair to say I’ve lost some of the details of my figure again. So I get them back, and then there’s the painting as it goes on as this constant dialogue between this set of realities and the more particular requirements of the figure and getting the figures done in a way that feels particular enough and yet is consonant in its making with the big gesture of the rain and the rainbow. So, we’ll see how that’s going to happen.

In the pursuit of that, I go from one tool to another, basic tools, but brushes, rollers, painting knives of different sizes and shapes. Here’s a painting knife that my father used to use. He had his father put a strong handle on it, so you could indeed really bear down and do things like this. So, with painting knives and brushes, and it’s not too radical in terms of the tradition of painting, and yet it affords as much free thinking as a person could possibly generate.

I’m trying to bring that rainbow down into here and I’m not liking that very much. As it turns out, I think it’s distracting from that center that I was talking about. So good idea. But you know, maybe it’s not a bad idea. Maybe it’s just too much of a good thing. So, I had a teacher at Cornell University in my graduate program who taught materials and methods, and he used to say over and over that the rag is a painter’s best friend. And wow, over the years, it’s turned out for me that that’s very true. Not in the sense of just wiping things out, but in the sense of modifying things and allowing softening things, muffling edges, dragging paint around a little bit.

So, I think I’m going to make this go the other way with this. Make that a little darker in there. And it takes me awhile, you know, and this is where painting isn’t just executing for me. It’s kind of like a process of partly trial and error, but partly a process of gaining or finding ways to amplify my original sensation and the idea. What I’m finding is that if I want this to be the center and I’ve made all of those same figures the same value and that’s fighting against my intention. And it took me now to realize it.

So, what I’m going to do is, I’m going to make as we get back here to the back, I’m going to make the boat, this figure less contrasted with its background than these figures here. And this figure less contrasted than this. And so right away I could see – notice I just like scribbling stuff in there – I’m in such a hurry to see what it’s going to look like. But if I scribble that stuff in there like that, not worry about the engine or the boat or anything like that, just with the idea of making this end of the boat more similar to this area back here. And I think I can see already that that’s going to be a pretty productive direction. That saves that contrast of ultimate black and these bright colors. It’s almost like the rainbow – the black is the opposite of the rainbow. So, I think already I can see, perhaps I could push it this way too. It could make this part a little darker. And it’s like breathlessly trying to get that to happen without worrying at all, at this stage, about what those figures are going to look like.

I’m going to make the back of that boat and the back figure blend with the land back here, barely distinguishable. And get rid of all those lines of distinction, I think. Wow. I think that’s really a better idea than I had before. And that came out of the process of painting. So, I’m not sure exactly what stand this guy should take. What happens if I put him into a dark yellow Mackintosh and take what I thought was the ultimate example of contrast and lose that since that figure is so prominent anyway? What if I lose this figure in the rainbow? By putting him into the yellow rain slicker that they often wear. Wow. You know, I don’t know. No, I think I like my original idea about having that figure dark, so I’m going to scrape that off.

So, I appreciate the kind of painting where the painter, visibly, even in the final image – what’s on display – is an image that seems to retain the potential of trial and error, you know, of something that’s being explored and invented at the moment as opposed to something that’s ready-made and executed. I’m going to make this figure a little smaller too. Let’s see what happens. Yeah, I think that doesn’t hurt at all to have that figure. And so, I can catch up with remaking that rainbow a little later and it gives me a chance to back light that guy. And then here’s where I think, probably, the painting begins to slow down quite a bit as you make all these changes at the beginning. And that’s a day’s work almost. And I’m to the point where I just really want to see what that’s like.

I might spend a little more time making that fish a little more accurate, there’s a lot of repainting. And the art of it is to keep it looking fresh so that in the end, maybe it has the verve of a child’s painting, which is all done at once and then left. Yet it has the complexity of all these other things that it’s possible to think about while we’re developing these images. So, I lost everything back there before and now I’m seeing what it’s like if I push back a little horizon line that pushes the boat forward. Um. Yeah, I don’t know. I don’t know. Maybe we got something here.

The hardest thing to me about art, whether it’s writing or maybe it applies to musical composing, I’m not a composer, certainly about visual art, the hardest thing is for the artist to see clearly what you’re doing. You know, you always get confused with what you intended to do. And it takes some time, physically I mean, just literally time off and to catch up with what you’ve actually done.

So, I kind of like that idea. And maybe it’s a little too generous to call that an idea. But what happens if we make it so from now on? The painting is about adjusting these areas to one another, and I kind of like that. The experience of intensifying this color of those hills as it gets close to the fish, because that’s another way of making this, keeping this, the heart of the painting. And that’s what I’m after above everything is keeping that the heart of the painting. I think up here, it probably wouldn’t hurt to darken that. And it probably wouldn’t hurt down here to enrichen and darken this too. And again, insert this continuity of there to there so that rainbow comes all the way down and that way the fish becomes kind of a nexus for the whole composition, maybe even more than the figure.

And maybe I even want to experiment with taking again this arc of the rainbow down all the way to here and somehow extending that dark down all the way to the bottom, so that the shaft of that rainbow, the big falling motion of it, is felt. Just felt. So, I think I’ve succeeded. I’ve succeeded disguising this figure so much it doesn’t even look like a figure anymore so I might try to get him back. He says, “Don’t forget me. I’m back here too, you know. I’m running the engine.”

That’s feeling grounded down here now, which I like. This is, even though they’re in the water, they’re sort of, they’re grounded here on Earth. And so that reminds us, that suggests to me that by making that darker, it groups with the backend and maybe the fish don’t have to be the dark things. The fish can be the light things in the dark water. That’s not something I explored in that drawing at all, but it might be worth trying here. So that kind of makes it into a geometry a little bit, and that gets at that unity that I had noticed earlier between the grouping of the fish and the boat and the fisherman. But it does it in a way that’s a little more assertive than I had originally imagined.

I’m wondering if all of those – what if those floats, some of them were light and some of them were dark? How come they all have to be light? And maybe they look dark against the light water. And I think that’s a much more interesting idea to have. That chain of forms, these little oval forms, go from light to dark to light again. So, as you travel along that line, they are transformed. Yeah, I’m losing that beautiful curve that I had up here. I think I’m losing that curve partly because I let my figure get a little small. So, I’m going to enlarge that figure. Yeah, my, that’s a big fish. He’s got a biggun. But that’s okay.

One of the reasons painters like me paint in broken brush strokes like this is so I can experiment with introducing a new color and still stay in touch with what was there before. It’s not like it was a mistake. It’s just like it’s a step. And so, I’m wondering here, as we get to this other sign, how, if that is supposed to introduce a hard line back there. This kind of broken stroke will suggest the landscapes there without ever having to bring it to one particular edge or contour of hill or something like that. And so, you know, I think I’m getting somewhere slowly with this and I may have to leave it alone pretty quick and I’m feeling that this is pretty much a day’s work on this particular painting.

Because it’s now time for me to really see what I’ve done and that may take a couple of days, or it may take a couple of weeks in order to feel like I’ve got some purchase on this to move forward with it again. So here I’m experimenting with introducing some kind of brightness and brilliance. The sense of the rainbow, and it seemed a little garish, so I knock it down a little bit and then we still get the focus on the heart of the beast there. And the sky is getting a little heavy, so break that. Then turn it into some distance and try for some feel of verticality in there, suggesting maybe some surrounding rain and moisture.

The fish is almost gone as that other boat comes into play and so I’ve got to fight for getting that fish back. And I like a lot of things about this, but it seems so active all over, in the way of taking one away from that center. So, this is a return through the brilliance in the silhouette of centering on that one fisherman at the bow of the skiff there and the fish in the water. So, it kind of works by pushing things backward and forward.

And here I think you know, I’m inspired by the shimmer of the rain and the rain drops and it gets to be too much. So, I smoothed that out and take it into a completely different direction and then reintroduce some of that choppiness. It’s going back and forth really. I don’t know what I’m going to have or what it means until I do it. So certain things – features and points of emphasis – recur, and as they do, gradually, through a kind of a trial and error process, get a bead on what is most important to the narrative. And I’ve even reversed the rainbow colors, experimented with that, changed the order around this being a metaphorical rainbow instead of a new one. And that’s pretty much the way it is right now, and I’d like to carry it just a little bit further.

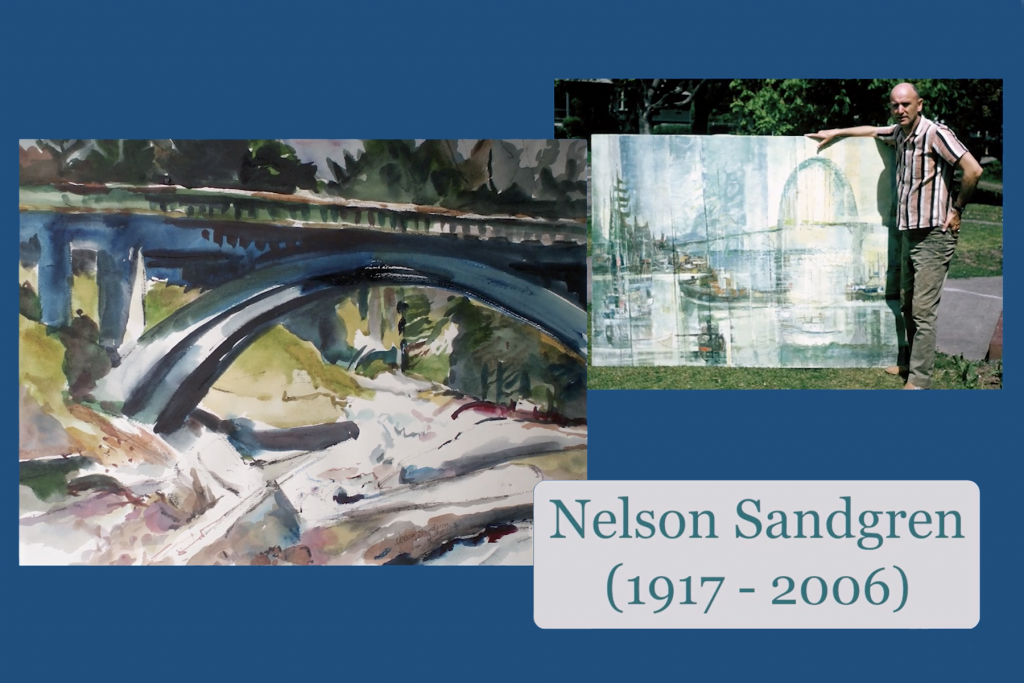

As I paint, I’m in dialogue with other artists who’ve helped me along the way and some of them I’ve never met. They lived hundreds of years ago, if not centuries ago. Some, like Monet, are closer. Claude Monet, the great French painter, of course, shares my territory – or I share his territory – in terms of making color light as brush strokes with pigments, gestures with pigment. Paul Cezanne said of him, “Monet is only an eye.” But god, what an eye. And, of course, he’s taught us about color and about refraction and reflection, and he returned to his homestead and constructed a large garden, Giverny, which people still visit. And of course, his last years of painting all the way into the 1920s were at Giverny, where he achieved this balance between the guide, the balance of a garden between nature and culture and human interaction with that nature. And he taught me about that balance. I seek a very different balance between natural features and cultural aspects, I guess you might say. And of course, I’ve painted different locale. Whereas Monet had Giverny, I have the Tuality Plains and the Oregon coast and the Cascades and the Steens and the Siskiyous, and I feel very much invited to incorporate all those subjects and so there’s a different flavor, but he’s an inspiration.

And some of those painters with whom I have a dialogue in my mind are actual dialogues. They’re available. Kathryn Cotnoir, born in 1952, living and painting, yet she lives with me. We’ve been married for 43 years and what she brings to her comments and her glances and her assessments and opinions about my work when I ask are just tremendous. Backgrounds in printmaking and drawing and, in the last couple of decades, painting. And we met at Cornell as graduate art students in Ithaca, NY, and have been helping each other with our, with each other’s work you know, ever since. And of course, some of the things she doesn’t say are just as important as the thing said. But there it is. That’s a life, you know, with another set of eyes, with a different set of interests and a different set of assumptions. And all painters are different that way.

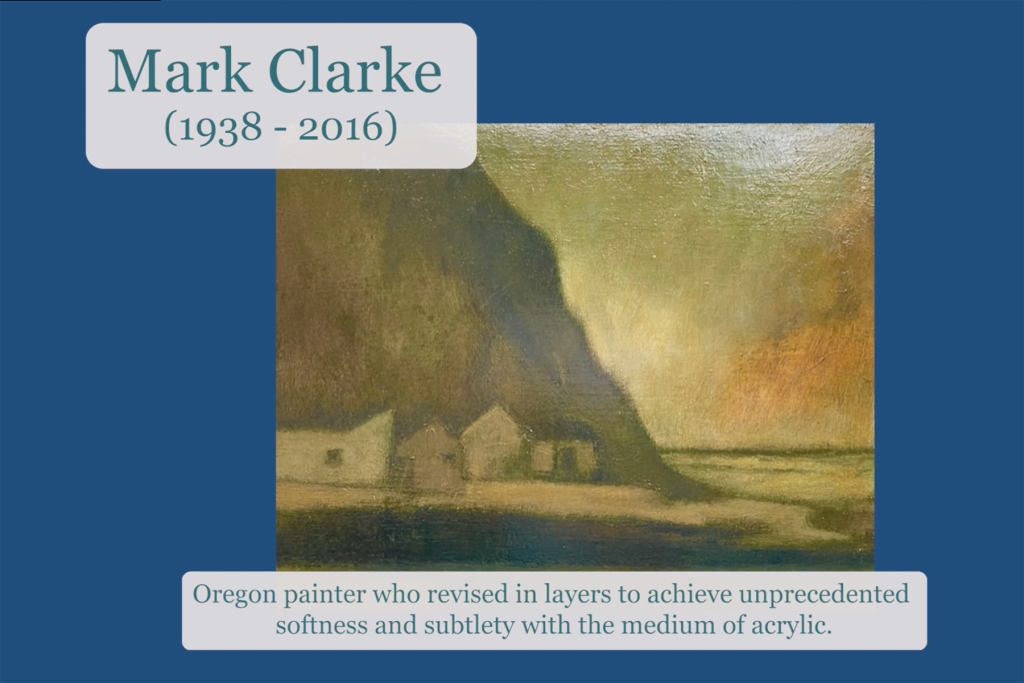

Sometimes when I’m painting, I feel, especially when I’m pushing a painting through various phases and changes on a trial and error basis, just to see what’s going to work best, Mark Clarke comes to mind. Mark Clarke was a Eugene painter. He started out as a student of my father’s. Eighteen years younger than my father was and 18 years older than I am or was and he just achieves incredible softness with acrylic and wonderful color of a kind that can only happen when the edges are soft and mysterious and lost in the physical working of the paint. So often beautiful work and a constant inspiration. I used to call Mark up when I was painting at the easel, and we talked for hours about this and that. A lot about painting and materials. And he was too nice a man to, say directly, offer me a critique of my painting at a certain point. The way he handled that was to one day give me a brush that was all bent and crooked, and all the bristles were messed up and he presents me this brush. He said, “Here’s a gift.” He said, “You’re going to love it. It won’t do anything you want it to do.” What a nice way of saying, “Son, soften your edges. Get rid of some of the detail. Make some choices here and open yourself to accidents.” And that’s how he did it – by giving me a brush. I love it. Something like that stays with me every day when I paint.

Help Kids Learn About Art With Lessons From Golden Road Arts

Golden Road Arts has developed a library containing free art literacy lessons and instructional tutorials. To see our latest content, watch our free art lessons here.

You can also donate to Golden Road Arts and help our mission of delivering the best free art content for children.